The Grief of Becoming Disabled — and the Possibility of Rebuilding a Full Life

Claire Wentz - caringfromafar.com

Losing one’s physical abilities can feel like losing an entire identity. Disability changes not only what a person can do but how they see themselves and the world. What follows can feel like grief — a mourning of the life that once was, the ease that once existed, the imagined futures that no longer fit. Yet within that pain lies a quieter truth: many people who become disabled eventually find new meaning and new ways to live fully.What You’ll Learn Here

● Grief after disability is real — and it’s not weakness.● Adaptation happens through both practical change and emotional repair.● Creativity, connection, and purpose can flourish through accessible tools and communities.● Healing involves redefining independence, not surrendering it.● Technology, art, and mutual support can turn constraint into expression.The Shape of Loss and the Work of Acceptance

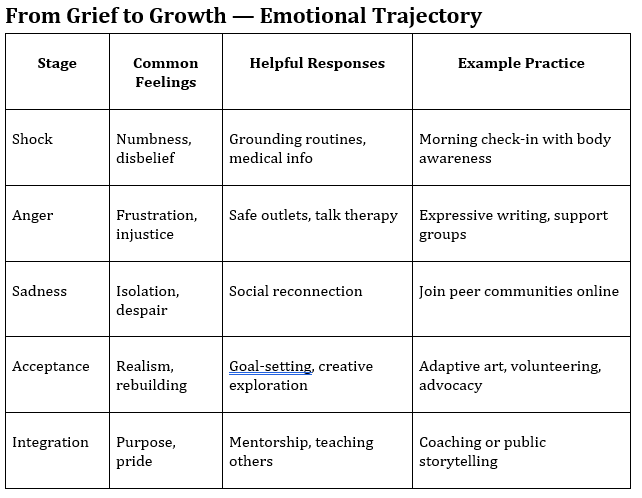

When disability enters a person’s life (through injury, illness, or a gradual decline), the first reaction often mirrors bereavement. There’s denial (“This can’t be permanent”), anger (“Why me?”) and deep sadness. Acceptance rarely arrives in a straight line.That grief is not just about the body. It’s about disrupted roles, social participation, and autonomy. People often mourn professional identities, physical freedom, or the small rituals of daily life. Recognizing this grief as natural is crucial.How People Begin to Rebuild Meaning

Recovery isn’t only medical. It’s psychological and social — a process of reimagining what life can hold. Many people describe three turning points:Acknowledgment: Facing the permanence of change, even when it hurts.Reconnection: Seeking community — online groups, local disability collectives, therapy, peer mentors.Reconstruction: Building new rhythms, interests, and identities that don’t depend on “returning to normal.”

This redefinition often leads to unexpected strength. In recognizing vulnerability, people also rediscover agency.A Few Ways People Find New Ground

After the initial shock, many survivors describe slow but tangible shifts:● Reframing “help” as interdependence, not dependency.● Learning adaptive techniques for hobbies and work.● Seeking therapy specialized in adjustment to disability.● Using assistive technologies — from voice tools to adaptive sports equipment — to reclaim autonomy.These steps don’t erase loss; they make space for growth beside it.Digital Art as Emotional Adaptation

For many adjusting to disability, expression becomes a bridge between past and future. Technology is increasingly making that bridge wider. Creative tools such as painting digitally with an AI painting generator now offer low-barrier, accessible ways to explore emotion and identity. With simple text prompts, users can turn ideas into images that mimic watercolor, oil paint, or abstract design.

Beyond aesthetics, this kind of tool helps transform emotional weight into visible form. It lets people play again — to externalize loss, explore new narratives of the self, and feel mastery over creation when control elsewhere may feel diminished.

How-To: Rebuilding a Meaningful Daily Life

Reconstruction begins with small, structured actions. Try these steps:

Name the Loss: Journal or talk about what specifically feels gone — this turns amorphous grief into something workable.

Set Adaptive Goals: Replace “I want to walk again” with “I want to move independently,” allowing different pathways to success.

Create a Support Web: Involve professionals (therapists, occupational specialists), peers, and loved ones.

Practice Compassion: Self-blame slows adaptation. Acknowledge effort, not just progress.

Engage Curiosity: Explore accessible hobbies, tech, or creative expression — discovery builds forward momentum.

When Adaptation Feels Impossible

There are times when progress halts. Fatigue, depression, or chronic pain can erode hope. At those points, the most vital act is reaching out — not because others have the answers, but because grief shared becomes bearable. Psychologists emphasize that belonging itself is medicine: peer groups reduce suicidal ideation and boost self-efficacy. Asking for help is not regression; it’s survival.

Living Fully in a Changed Body

Adaptation is not denial. It’s an act of creative realism — of saying, “I will build a life from what remains.” Many people living with new disabilities describe a paradoxical expansion of empathy and perspective. They learn to notice joy in the margins, to craft meaning deliberately, to celebrate small wins that others rush past.

Fullness after loss looks different, but it is fullness all the same.

Real Questions, Honest Answers: The “Reframing Life” FAQ

People rebuilding after disability often ask the same questions. Here’s what experience and research suggest:

1. How long does grief last after becoming disabled?

There is no expiration date. Emotional adaptation can take months or years. What changes is not that grief disappears, but that it coexists with new forms of purpose and peace.

2. Can therapy really help with something physical?

Yes. Cognitive-behavioral and acceptance-based therapies reduce depression and improve function by teaching coping skills and realistic goal-setting. Emotional health strengthens physical adaptation.

3. What if my friends or family don’t understand my new needs?

Education and boundaries help. Sharing specific explanations (“I need more rest between activities”) is more effective than general statements of frustration. Support groups can fill gaps where loved ones can’t.

4. Is it normal to feel guilty for needing help?

Completely. Our culture overvalues independence. Reframing help as collaboration reframes self-worth: interdependence is human, not failure.

5. How can technology actually improve my daily life?

Adaptive tech — from speech-controlled devices to digital art platforms — expands access, connection, and creative outlets. Explore tools that reduce strain and restore self-expression.

6. Can a meaningful career or relationship still exist?

Absolutely. Many adapt through flexible work, advocacy, or remote opportunities. Relationships often deepen through honesty and shared growth.

Conclusion

Becoming disabled can shatter identity — but it can also reconstruct it. The grief that follows is not a dead end; it’s a passage. By facing loss, cultivating creativity, and accepting interdependence, people learn that a changed body is not a broken life.

There are still stories to be told, art to be made, love to be given, and joy to be found — differently, but no less real.